Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

Prologue to Order Number 11 |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Aug 20 2013 |

On June 9, 1863, Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. had been given command of the Federal District of the Border in the Department of the Missouri. His instructions were simple; protect the District’s citizens from the depredations of war. But this meant putting a stop to the guerrilla war occurring along the Missouri-Kansas border, a task easier said than done. Ewing figured he had two problems. The first was jayhawkers crossing the border from Kansas to plunder Missouri homesteads. The second were pro-Southern Missourians attacking Federal troops and pro-Union civilians in Missouri. And recently these Missouri guerrillas, particularly those led by William C. Quantrill, had been crossing the border into Kansas to plunder Kansas towns.

On June 9, 1863, Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. had been given command of the Federal District of the Border in the Department of the Missouri. His instructions were simple; protect the District’s citizens from the depredations of war. But this meant putting a stop to the guerrilla war occurring along the Missouri-Kansas border, a task easier said than done. Ewing figured he had two problems. The first was jayhawkers crossing the border from Kansas to plunder Missouri homesteads. The second were pro-Southern Missourians attacking Federal troops and pro-Union civilians in Missouri. And recently these Missouri guerrillas, particularly those led by William C. Quantrill, had been crossing the border into Kansas to plunder Kansas towns.

Ewing only had about 2,500 cavalry troops under his command in the District of the Border. By August, Ewing had decided to disperse his troops in garrisons at towns along the border. In this way his forces to move quickly to the support of other garrisons if needed. He knew his military force was insufficient for the task so he began to think of another approach to solving his problem.

Over the next couple of months, Ewing became convinced that many, if not most, of the Missouri civilians in his district were aiding and abetting the guerrillas. Ewing began to formulate a plan for removing these pro-Southern civilians from the district. On August 3, Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. wrote a letter to the headquarters of the Department of the Missouri in which he described a plan to evict the worst of the pro-Southern families from the border counties. He explained his plan and asked for authorization to execute it from his superior officer, Major-General John M. Schofield.

Two-thirds of the families [here] are of kin to the guerrillas, and are actively and heartily engaged in feeding, clothing, and sustaining them. The presence of these families is the cause of the presence there of the guerrillas. I can see no prospect of an early and complete end to the war on the border, without a great increase of troops, so long as those families remain there.

Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. wanted to expel these families and send them south to the Confederacy. He felt the guerrillas would follow them south. Ewing also wanted to identify any slaves belonging to “persons engaged in rebellion” and escort them to locations where, as free men, they could support the Union war effort. Major-General Schofield concurred and, on August 14, authorized Ewing to implement the plan.

Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. wanted to expel these families and send them south to the Confederacy. He felt the guerrillas would follow them south. Ewing also wanted to identify any slaves belonging to “persons engaged in rebellion” and escort them to locations where, as free men, they could support the Union war effort. Major-General Schofield concurred and, on August 14, authorized Ewing to implement the plan.

The major-general commanding authorizes you to make preparations for transporting such of them as you deem it necessary to dispose of to some point to be selected hereafter … collect them at one or more points on or near the Missouri River, where they can be temporarily guarded and quartered … the number to be transported should be as small, as possible, and should be confined to those of the worst character.

Now that he had authorization from his commanding officer, Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. issued District of the Border, General Orders, No. 9 on August 18, 1863. Ewing ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Walter King, Fourth Regiment, Missouri State Militia to

-

Identify slaves who want to leave Missouri

-

Slaves must belong to Missourians who have given aid and comfort to enemy

-

Federal troops will provide subsistence and escort these slaves to safety

-

Any slaves fit for duty and willing to enlist will be sent to Kansas City

Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. also issued District of the Border, General Orders, No. 10 on August 18, 1863. This order was a shift in the Federal policy meant to remove the civilians that provided support to the guerrillas. This order was different because the civilians were now guilty just because they were relatives of known guerrillas. The Federal authorities did not have to prove them guilty of a crime. Understandably, the guerrillas were outraged by the order to remove their families from Missouri. The order had the following key provisions:

-

Arrest individuals who willfully aid and encourage guerrillas

-

Notify families of known guerrillas to leave Missouri

-

Banish men (and their families) who have taken up arms against the Union

The implementation of Orders Number 9 and 10 led to a tragedy for some southern families. Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. actually began to implement his Order Number 10 before he officially issued the order on August 18. An announcement of the order was published in the Kansas City Journal newspapers on August 13.

You may drive [the guerrillas] out again and again, but they will come back, so long as their families remain … The open Union men have nearly all been obliged to leave the country and congregate in the towns, while the bushwhackers and their sympathizers and abettors remain to till the soil … General Ewing … will immediately arrest and send out of the country the family of every known bushwhacker in his District.

Some of the first relatives arrested were the sisters (Josephine, Mary and Jennie) of Bill Anderson, one of Quantrill's lieutenants. They were arrested on August 11 at their home just south of Kansas City. On the way back to Kansas City, the squad of 14 Federals and their prisoners were ambushed by three guerrillas, one of whom may have been Bill Anderson. No one was hurt in the ambush and they soon arrived in Kansas City where the three sisters were placed on the second floor of a three-story brick building at the corner of Fourteenth Street and Grand Avenue. Other women that were arrested and confined in this building were Charity McCorkle Kerr and Nannie Harris McCorkle (sister and sister-in-law of John McCorkle) and Susan Crawford Vandever and Armenia Crawford Selvey (cousins of Cole Younger). All of these women were being held until they could be sent to St. Louis and then banished from Missouri.

Some of the first relatives arrested were the sisters (Josephine, Mary and Jennie) of Bill Anderson, one of Quantrill's lieutenants. They were arrested on August 11 at their home just south of Kansas City. On the way back to Kansas City, the squad of 14 Federals and their prisoners were ambushed by three guerrillas, one of whom may have been Bill Anderson. No one was hurt in the ambush and they soon arrived in Kansas City where the three sisters were placed on the second floor of a three-story brick building at the corner of Fourteenth Street and Grand Avenue. Other women that were arrested and confined in this building were Charity McCorkle Kerr and Nannie Harris McCorkle (sister and sister-in-law of John McCorkle) and Susan Crawford Vandever and Armenia Crawford Selvey (cousins of Cole Younger). All of these women were being held until they could be sent to St. Louis and then banished from Missouri.

The building in which they were confined was poorly built, unsafe, and being weakened by another building leaning against it. On the afternoon of August 13, the building collapsed. Susan Vandever, Armenia Selvey, Josephine Anderson and Charity McCorkle Kerr were killed immediately. Another woman later died from her injuries sustained during the collapse. Mary Anderson was injured so badly that she was crippled for life. Jennie Anderson had both of her legs broken and suffered an injury to her back.

Unfortunately, this tragedy could have been prevented if Brigadier-General Thomas Ewing, Jr. had acted more quickly. A Union surgeon named Dr. Joshua Thorne had visited the prison in order to treat the women prisoners. After his visit, Dr. Thorne reported to Ewing's headquarters that the building was unsafe and all prisoners confined there needed to be moved to someplace more safe. But no action was taken as a result of this advice. As you might expect, there was a tremendous amount of controversy surrounding this. Southern sympathizers made claims that Federal troops had purposefully dug in the foundation, undermining it. Pro-Union elements said that the prisoners had dug into the foundation trying to escape.

John McCorkle wrote about the tragedy that befell his family when the Union prison building collapsed and the impact it had on the Missouri Guerrillas:

John McCorkle wrote about the tragedy that befell his family when the Union prison building collapsed and the impact it had on the Missouri Guerrillas:

The Federal soldiers at Kansas City … were guilty of one of the most brutal and fiendish acts that ever disgraced a so-called civilized nation … This foul murder was the direct cause of the famous raid on Lawrence, Kansas. We could stand no more. Imagine, if you can, my feelings. A loved sister foully murdered and the widow of a dead brother seriously hurt by a set of men to whom the name assassins, murderers and cutthroats would be a compliment.

Josephine Anderson is buried in Union Cemetery, 227 East 28 Terrace in Kansas City, Missouri 64108. McCorkle quoted a Mrs. Flora Stevens who spoke at the grave of Josephine Anderson:

Josephine Anderson is buried in Union Cemetery, 227 East 28 Terrace in Kansas City, Missouri 64108. McCorkle quoted a Mrs. Flora Stevens who spoke at the grave of Josephine Anderson:

There were nine of these girls in the prison at 1409 Grand Avenue, when it fell … These girls … had been arrested because they were Southern sympathizers … waiting to be banished … The plastering had been falling all day and the girls were in a panic … [There were] cries … that the roof was falling … Janie Anderson … tried to escape through a window, but a twelve pound ball that had been chained to her ankle held her back and both her legs were broken … Josephine Anderson could be heard calling for someone to take the bricks off her head. Finally her cries ceased.

George Caleb Bingham despised Thomas Ewing, Jr. and argued that the Federals had deliberately weakened the building, bringing on its collapse. Bingham claimed that the Federal authorities had undermined the building’s foundation. Bingham wrote the following article that was published in the Washington Sentinel on March 9, 1878.

That the death of these poor women crushed beneath the ruins of their prison was a deliberately planned murder … The fact that no inquiry was instituted by General Ewing in relation to the matter and that no soldier was arrested, tried or punished for a crime … renders it impossible for him to escape responsibility.

There is a Historical Marker [ Waypoint = N39 05.774 W94 34.855 ] located at the southeast corner of 14th and Grand in Kansas City, Missouri. The Marker’s text

There is a Historical Marker [ Waypoint = N39 05.774 W94 34.855 ] located at the southeast corner of 14th and Grand in Kansas City, Missouri. The Marker’s text

Very near here at 1425 Grand Avenue during The Civil War, a tragedy occurred that was to intensify the ferocious hatred of the Border guerrillas for the Union forces. Under Union General Ewing's orders, the guerrillas' women were imprisoned in a large three-storied brick building owned, but not then occupied by artist, George Caleb Bingham. About two o'clock on Friday, August 14, 1863 the weakened building collapsed injuring many of the female inmates. "Christie" McCorkle Kerr, Susan Selvy Vandiver, Arminia Selvy and Josephine Anderson, sister of "Bloody Bill" Anderson, were killed. Also many female relatives of the men with Quantrill were injured. Mary Anderson, Armenia Whitsett Gilvey, Mollie Grindstaff, and Nanie Harris, all injured, had close relatives with Quantrill and the Younger brothers.

On the news of the tragedy reaching Quantrill's men in the brush, they were wild. Also on August 18th, General Ewing issued General Order No.10, banishing the guerrillas' families from the state. Coupled with the death and injury in the collapse, then banishment of their women, the guerrillas seemed to scream for retaliatory measures.

Friday, August 21, 1863 dawned hot and clear as Quantrill, with 310 men perpetrated the Lawrence Massacre. In two hours close to 150 male citizens of Lawrence were killed, several only young boys. Not one Lawrence woman was injured. 185 buildings were destroyed. Eighty widows and 250 orphans were left crying in the dusty streets. By 9 o'clock the massacre was over and the guerrillas retreated. A tragedy here and General Order No. 10 were blamed for the Lawrence Massacre.

Image Credits

-

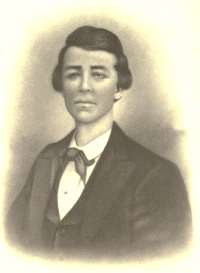

Thomas Ewing, Jr. [LC-DIG-cwpbh-03226, image courtesy of the Library of Congress]

-

William C. Quantrill from Quantrill Border Wars by Connelley

-

John M. Schofield [LC-DIG-cwpb-05934, image courtesy of the Library of Congress]

-

William T. Anderson from Three Years with Quantrell by McCorkle

-

Nannie Harris McCorkle and Charity McCorkle Kerr from The Story of Cole Younger, by Himself

-

Josephine Anderson Grave by Dick Titterington

-

John McCorkle from Three Years with Quantrell by McCorkle

-

Union Prison Collapse Historical Marker by Dick Titterington

References

Castel, Albert E. William Clarke Quantrill : his life and times. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999. [p. 118-120]

Connelley, William E. Quantrill and the border wars. Cedar Rapids, Iowa: The Torch Press, 1910. [p. 299-300]

Hale, Donald R. They Called Him Bloody Bill: The Life of William Anderson Missouri Guerrilla. Clinto, Missouri: The Printery, 1975. [p. 8-9]

McCorkle, John. Three years with Quantrill : a true story told by his scout, John McCorkle. Armstrong, Missouri: Armstrong Herald Print, 1914. [p. 120-123]

Nichols, Bruce. Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri: Volume II, 1863. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2007. [p. 208-210]

United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 volumes in 4 series. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Series 1, Volume 22. [p. 428-429, 450-451, 460-461]

Dick Titterington, August 20, 2013.

Last changed: Aug 20 2013 at 4:05 PM

Back