Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

The Campaign in Missouri in September and October, 1864 by Brevet Maj. Gen. John B. Sanborn: Part 1 |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Aug 02 2018 |

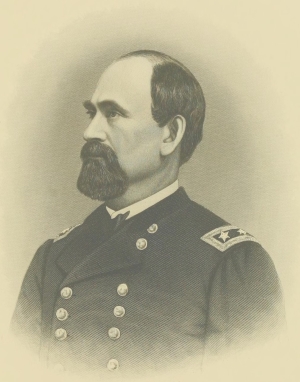

In the summer of 1864, Brig. Gen. John B. Sanborn was in command of the District of Southwest Missouri, Department of the Missouri, with his headquarters in Springfield. Ordered to Jefferson City in October to help defend the state against a Confederate invasion led by Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, Sanborn arrived there “with all the available cavalry force of the command and one battery of light artillery,” arrived there shortly before the Confederates did. After Price continued west, Sanborn was placed in command of a “corps of observation” and shadowed the Confederates movement west. When Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton arrived to assume command of the Provisional Cavalry Division, Sanborn assumed command of the 3d Brigade. As brigade commander, Sanborn led his men in the Second Battle of Independence, the Battle of the Big Blue at Byram’s Ford, the Battle of the Mounds near Trading Post, Kansas, and the Second Battle of Newtonia. On October 14, 1890, Sanborn delivered an address entitled The Campaign in Missouri in September and October, 1864 to the Minnesota Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.

In the summer of 1864, Brig. Gen. John B. Sanborn was in command of the District of Southwest Missouri, Department of the Missouri, with his headquarters in Springfield. Ordered to Jefferson City in October to help defend the state against a Confederate invasion led by Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, Sanborn arrived there “with all the available cavalry force of the command and one battery of light artillery,” arrived there shortly before the Confederates did. After Price continued west, Sanborn was placed in command of a “corps of observation” and shadowed the Confederates movement west. When Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton arrived to assume command of the Provisional Cavalry Division, Sanborn assumed command of the 3d Brigade. As brigade commander, Sanborn led his men in the Second Battle of Independence, the Battle of the Big Blue at Byram’s Ford, the Battle of the Mounds near Trading Post, Kansas, and the Second Battle of Newtonia. On October 14, 1890, Sanborn delivered an address entitled The Campaign in Missouri in September and October, 1864 to the Minnesota Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.

Source: Sanborn, John B. “The Campaign in Missouri in September and October, 1864.” In Glimpses of the Nation’s Struggle Third Series, 135–204. St. Paul, MN: D. D. Merrill Company, 1893. https://archive.org/stream/glimpsesnations00neilgoog#page/n141/mode/1up.

The invasion of Missouri, in the months of September and October, 1864, by a Confederate army from Arkansas, under the chief command of Major-General Sterling Price, was an event of the War of the Rebellion commonly denominated “The Price Raid.” Taking place at a time when public attention was attracted to other quarters, where affairs of greater moment were in progress, and occurring in a field somewhat remote from frequent communication with the news centers, and where consequential events were unlooked for, the real character of this enterprise has been generally imperfectly understood, and its importance greatly underestimated- The objects for which the expedition, on the part of the Confederates, was undertaken were, at the time and under the circumstances, of much importance to them and correspondingly of great danger to the Union cause. The campaign forced upon the Federal troops by the invasion was a series of rapid and difficult marches, perilous undertakings, daring and gallant exploits, hot and deadly fighting, and in the end resulted in complete success to the Union arms and great advantage to the Union cause. To describe the campaign generally, and to narrate some of its incidents, is the object of this paper.

In the latter part of the month of August and the first part of the month of September, 1864, when the plan of the invasion was conceived and determined upon, the main Confederate armies east of the Mississippi were sadly in need of help and cooperation. Lee was staggering at Petersburg under the heavy and incessant blows of Grant; Atlanta was, as Sherman said, “ours, and fairly won”; and Hood had inaugurated his offensive campaign to the rear of Sherman, designing, as he avowed, to “push for the Ohio”—a bold venture, but not without grounds and warrant, and which came nearer being successful than is commonly believed. Thomas had been left to “look after Hood,” and Thomas, surveying the scene with his clear, calm eyes, had announced that he must be strengthened with men and munitions before he should be able for the task set him. General A. J. Smith’s Corps from northern Mississippi was ordered to reinforce Thomas, and these were all the troops that could be given him. The other armies had enough work to do in their respective districts.

The Confederate army of the Trans-Mississippi Department, then under the command of Lieutenant-General E. Kirby Smith, was practically inactive, and had been so for some time. Davis, in August, had ordered Smith to cross the Mississippi, where and as he could, and to come with the greater and better part of his army to Richmond and Petersburg to the help f Lee; but it was impossible to obey such an order. Understanding the general situation fairly well, Smith and his generals believed that a diversion with their forces—then in various portions of Arkansas—if made suddenly in Missouri, would employ for a considerable time thousands of Federal soldiers who otherwise would be sent to Thomas, and thus enable Hood to “get in his work.”

Moreover, it was believed that the presence of a well-organized Confederate army in Missouri would arouse the Rebel element in that State, bring out swarms of recruits, and thus enable the army of invasion to become an army of occupation—after having picked up the numerous depots of supplies scattered throughout the southern and central portions of the State, and after having captured the arsenal and stores at Fort Leavenworth, known to be without adequate guard and protection. The movement, too, if swift enough, would accomplish the capture of St. Louis, long enough at least to “loot” it of all the invaders needed. Jefferson City, the capital of the State, could be—indeed, must be—taken, and the inauguration of the alleged Confederate “ governor,” Hon. Thomas C. Reynolds, performed with due pomp and circumstance, as became his state!

Once fairly within Missouri, the invaders meant to secure themselves south of and along the Missouri River, with their eastern outposts near Jefferson City, and a line of communication open to Arkansas and the Indian Territory by way of the Kansas border. It was confidently believed that by the assistance of the recruits in Missouri, who were expected to flock in by thousands, the army would be entirely able to maintain itself in the State through the winter against any force likely to be sent against it Much reliance was placed, especially by Generals Price and Marmaduke, upon the Rebel-sympathizing secret orders of the “ Knights of the Golden Circle,” “ American Knights,” or “Sons of the South,” known to be numerous in Missouri, and said to be longing for an opportunity to shake off the “ Lincoln despotism,” under which they had lived so long, and to enroll themselves under the banner of the “Stars and Bars.” If, however, the main object of the invasion should fail, a vast amount of supplies could be secured during the progress of the invasion, and these could be carried away into Arkansas should it be necessary to retreat, and the spoil and the recruits obtained would of themselves amply compensate for the trouble and expense incurred.

The objects, then, to be accomplished by the Confederate government were fourfold, and in the order of their importance were as follows:

1st. To create a diversion of Federal troops from General Thomas, then resisting General Hood’s advance into Tennessee, and thereby enable Hood to overpower this Federal army and drive it across the Ohio River, and thus regain what had been lost by the Atlanta campaign.

2d. To destroy the supplies accumulated at Kansas City, Fort Leavenworth, and Lawrence, and, as far as possible, capture and break up the Federal forces on duty in Missouri and Kansas.

3d. To recruit the Confederate army from the disloyal ranks of the people of Missouri, and add to its numerical strength from ten to twenty thousand men, and arm, equip, and supply them from the ordnance, commissary, and quartermaster departments of the posts and places captured.

4th. To inaugurate a State government in Missouri and declare it to be one of the States of the Confederacy, and issue bonds and do other acts that a State government lawfully established may perform.

The duty of the Federal generals was to thwart these purposes as far as possible, and destroy or capture the Rebel forces.

At this time Missouri was without any Federal army proper, and with but comparatively few troops, which were scattered at small posts through the State. There were not above five thousand regular volunteers in the State, of all arms.The State was held in the main by a cavalry organization called the Missouri State Militia (or M. S. M.), consisting of fourteen regiments armed, equipped, and paid by the Federal government, but not liable for service outside of the State. There was also the Enrolled Missouri Militia (or E. M. M.), composed of the able-bodied male citizens of the State, liable to military duty; but this organization, which was wholly in the State service, was only called to duty in emergencies and for brief periods—except that from the entire number, some fifty thousand, four regiments had been detailed for continual service, which were termed the Provisional Militia (or P. M. M.). Nearly all of the military posts of the State were garrisoned by the M. S. M. or the P. M. M.

General Rosecrans had been for some time the commander of this department, and the State having been practically depleted of troops, he obtained permission from the War Department to raise new volunteers to meet the exigencies of the situation. Under this permission about ten regiments, complete and incomplete, of one-year volunteer infantry, had been organized in July and August, but were practically not in service, being in camps of instruction in various parts of the State. Crops had been fairly good that year, the harvest had been gathered, the corn was ripening, and the opportunities for a raid were all that could be desired. I have been thus particular in describing the Rebel plans and purposes as they appeared then, and have been detailed since the war by certain ex-Confederate generals, and in referring to the situation, in order that the incidents of the campaign may be better understood.

As soon as the expedition to Missouri was determined upon by General Kirby Smith, whose headquarters were at Washington, Ark., he set about finding a proper officer to lead it. It was settled that the force should be composed of cavalry and artillery; for obvious reasons infantry was not wanted. General S. B. Buckner was first offered the command, but declined it on account of his unwillingness to lead cavalry. Generals Marmaduke and Shelby, both Missourians, and both very dashing and plucky officers, were considered too young to be placed over the officers who would of necessity command the divisions and brigades of the invading army, and at last General Price was selected. The chief reason for this selection was the supposed influence of General Price in Missouri and the popularity of his name. “ Old Pap,” as General Price was familiarly known, was unquestionably very popular with the Rebel masses, and he was—or rather had been—a very capable soldier; but he was growing old and corpulent, was almost incapable of horseback exercise, and a younger and more active commander might upon the whole have served General Smith better.

A little time was spent in selecting the route. It was proposed to enter the State at the southwest corner, pass rapidly up the Kansas line to Fort Leavenworth, seize that post, and then turn eastward into Missouri; but General Marmaduke has left on record the statement that one reason for the rejection of this route was this: “ That the southwestern corner, which was in the district commanded by General John B. Sanborn, with headquarters at Springfield, was well guarded, and there would be some hard and very stubborn fighting before the gates could be entered, and this might occasion a fatal delay.”

It was my judgment then, and has ever since been, that it was better military strategy to enter the southeastern portion of the State. In this movement, St. Louis, Pilot Knob, Rolla, and other points accessible by railroad would be threatened, and larger forces drawn at once away from General Thomas, which would at once be passed by this mounted force and thrown to the rear to pursue for days without result; while an invasion from the southwest would meet with strong resistance from the start, and the Federal forces, if defeated in the first engagements, would fall back upon constantly accumulating reserves, until strong enough to deal a stunning and overwhelming blow that would prevent the escape of the Rebel army from the State at all.

It was the impression of General Rosecrans that my district and command would be first attacked. About ten thousand men of all classes and arms—by calling out the militia—would have been available in action, and this gave some assurance of a successful resistance. The losses on both sides would have been serious. The days that the Rebel army remained at Batesville were days of anxiety to us, as all scouts brought back the same word, that when the next movement would be made it would be upon Springfield by forced marches. At Springfield everything was ready for action. It was finally concluded to enter at the southeast comer, move rapidly to and up the Iron Mountain Railroad towards St. Louis, further movements to be decided by circumstances.

The army of invasion concentrated first at Tulip, Dallas County, Ark., on the 30th of August, 1864. Afterwards, on the 16th of September, there was another concentration at Batesville, Ark. When the force had been finally organized at Batesville, it was composed of three divisions, two of Missourians and one of Arkansans. The Arkansas troops formed the first division, composed of Cabell’s, Slemmon’s, Dobbins’s, and McCray’s brigades, about five thousand strong, with four pieces of artillery, and commanded by Major-General James F. Fagan. The second division was commanded by Major-General John S. Marmaduke, and composed of the brigades of General John B. Clark, Junior (recently Clerk of the U. S. House of Representatives), General M. Jeff. Thompson, and Colonel Thomas W. Freeman, and a four-gun battery—in all about four thousand men. The third division was commanded by Brigadier-General J. Q. Shelby, and consisted of two brigades commanded by Colonels David Shanks and S. D. Jackman, with Collins’s four-gun battery—in all about three thousand. Thus the total strength of the Confederates, at the time of the concentration at Batesville, was about twelve thousand men and twelve pieces of artillery. This force was, however, rapidly increased as the invasion progressed into Missouri, until finally the army numbered about twenty thousand armed men, with about two thousand unarmed recruits. From Batesville the army moved to Pocahontas, near the Missouri line. Here four days were spent in shoeing mules and horses, repairing wagons, issuing ammunition, and arranging everything necessary.

On the 20th of September the army started from Pocahontas, Shelby’s Division on the extreme left, Marmaduke’s on the right, and Fagan, with the commander-in-chief, in the center. With General Shelby’s staff, as a volunteer aide, was the Confederate “governor” of Missouri, Hon. Thomas C. Reynolds. The advance was somewhat slow, but sufficiently rapid to enable the invaders to capture the towns in southeastern Missouri as fast as they came to them. Doniphan, Patterson, Fredericktown, Farmington, and other towns in the southeast were taken, and their garrisons, consisting of small detachments of militia, either driven off or made prisoners. The Iron Mountain Railroad was attacked, and portions of it destroyed- Shelby took Potosi, with its garrison of seventy-five men.On the 26th Ironton and Pilot Knob were invested. Here was a Federal force of twelve hundred, under General Thomas Ewing, who had been sent to the place by General Ro sec ran 8. At Pilot Knob, also, there was a small fort called Fort Davidson, in which there were some heavy guns. On the 27th Ewing sustained a terrific assault from portions of Fagan’s and Marmaduke’s Divisions, which advanced against the fort on foot, supported by a brisk artillery fire-from their own batteries on commanding situations. Two assaults were made, both of which were repulsed. That night Ewing spiked his guns, destroyed his magazine and supplies, and finding his chosen line of retreat northward, by way of Potosi, blocked, he retreated westward towards Rolla, where General John McNeil was in command with a small brigade of M. S. M. and the Seventeenth Illinois Cavalry. In the fighting about Pilot Knob the Confederates lost about three hundred men in killed and wounded, and three days’’ time. Ewing lost twenty-eight killed and about sixty-wounded. The Confederates were able to replace the-men they lost by the accession of about five hundred recruits, which they received at Pilot Knob. By this attack General Price had demonstrated the formidable character of his movement, and really secured the first great object of his campaign—the diversion of Federal troops from General Thomas.

On his retreat Ewing had about one thousand infantry and a field-battery. Accompanying him was Colonel Thomas C. Fletcher, the Republican candidate for governor in the campaign then pending, and whose person the Confederates were anxious to secure. Some miles out from Pilot Knob, Ewing turned sharply to the north, and pushing on struck the southwestern branch of the Pacific Railway at Harrison station, where he seized and extended some temporary breastworks which had been constructed by the militia, and. prepared to fight until reinforced. He had marched, sixty miles in thirty-six hours, his men were well-nigh exhausted, and his command was encumbered by a host of Union refugees, white and black. He had been pursued by Marmaduke and Shelby, but his route, through a semi-Alpine country, had been mainly along a high ridge, where the enemy could not flank him, and he had easily repelled every assault on his rear. At Harrison he was again attacked by Shelby, but after an investment of thirty hours the Confederates withdrew, and the Seventeenth Illinois Cavalry, under Colonel John L. Beveridge—since Governor of Illinois —sent by me from Rolla, came to his relief. Shelby having gone towards St Louis, Ewing and Beveridge marched to Rolla, then the terminus of the railroad. The Confederates were now well up in the vicinity of St. Louis. Their extreme advance was within sight of the spires of the city.

In the meantime our forces had not been idle and inactive. General Rosecrans had apprehended an invasion for some time. The “ Knights of the Golden Circle ” in Missouri had given him perhaps an undue amount of anxiety and concern, and he had arrested and imprisoned a number of them, including the Belgian consul at St Lotus, who was said to be the “grand mogul” of the order in the State. The movements of these gentry and the frequent unguarded declaration of Rebel women to their Union neighbors that “our time will soon come,” and the sudden warming into life of the entire Rebel element of the State, had made Rosecrans anxious and suspicious, and his spies had scented the real danger.

On the 3d of September General C. C. Washburn, at Memphis, sounded the alarm to Rosecrans by information that the force under Shelby, at Batesville, Ark, was about to be joined by another, under General Price, for the invasion of Missouri. On the 6th General A. J. Smith, passing Cairo with a division of infantry, on the way to General Sherman, Rosecrans telegraphed General Halleck the state of affairs, requesting orders for Smith’s Division to halt at Cairo and wait until the designs of the enemy could be ascertained. On the 9th Smith was ordered by Halleck to operate against Price, but deeming it impracticable to penetrate a hundred or more miles into the interior of Arkansas or Missouri with a small column of infantry in pursuit of a large force of cavalry, whose exact whereabouts and intentions were still unknown, he decided to move his command by water to a point near St. Louis, from whence he could readily move by rail or river, and await Price’s movements. Accordingly he came up the river to near St. Louis, and on the 26th of September, while the battle of Pilot Knob was in progress, Rosecrans sent him, with two brigades, to a point on the Iron Mountain Railroad, directing him to proceed as far towards Pilot Knob as compatible with a certainty that the enemy would not get between him and St. Louis. On the 28th, when information of Ewing’s fight at and retreat from Pilot Knob had reached him, General Smith being already confronted by Shelby’s Rebel division, which was moving to his west and north, apparently to cut him off, withdrew from De Soto, and moved to the north bank of the Meramec River, within ten or fifteen miles of St. Louis.

General Washburn had sent General Joe Mower’s Division, of Smith’s Corps, and Winslow’s Brigade of cavalry across the Mississippi into Arkansas in pursuit of Price, and this force made a long, stem chase, toilsome and arduous, after the Rebel column, being all the time several days’ march in the rear, until at last, worn out and disgusted, Mower turned eastward, and reached the Mississippi at Cape Girardeau, Mo., where his command took steamboats and came to St. Louis on the 8th and 9th of October.

Meanwhile, General Rosecrans, at St. Louis, had been making all possible preparations to meet and resist the enemy. When the invasion began he had only about six thousand five hundred mounted men in the department, and these were scattered over a country four hundred miles in length by three hundred in breadth. The militia in service in central and northern Missouri were kept busy at home; for just before General Price left Arkansas he sent couriers to the numerous Rebel guerrilla bands along the Missouri River, notifying them of his approach, and instructing them to cross the river, to harass the country, and by every means possible to keep the Union troops actively employed on the north side of the river. It is a fact that though the Confederate leaders in the Trans-Mississippi Department pretended to deprecate guerrilla warfare, and refused to furnish regular commissions to the leaders of the numerous bands of guerrillas and bush-whackers in Missouri, yet they looked upon them as auxiliaries, and uniformly availed themselves of their services whenever the occasion was presented.

Soon after the receipt of Price’s instructions, the guerrillas mid bush-whackers were swarming in the counties along the north side of the Missouri, under the leadership of Quantrill, Bill Anderson, George Todd, John Thrailkill, and other noted and infamous chieftains. The county-seats of four counties were attacked; there were dozens of sharp skirmishes, and innumerable atrocities were perpetrated. The guerrillas were splendidly mounted, and went armed to the teeth and fought to the death. On the 27th of September, when the battle of Pilot Knob was in progress, four hundred of these miscreants, led by Todd, Thrailkill, and Anderson, captured the village of Centralia, on the North Missouri Railroad, eighty miles northwest of St. Louis, took from a train twenty-three sick and furloughed Federal soldiers, robbed the express and mail car and all the passengers, burned the train, and inhumanly murdered the prisoners. The same day this force was attacked two miles from Centralia by a force of one hundred and fifty-five men belonging to the Thirty-ninth Missouri Infantry—one of the new regiments then organizing—and in the fight that ensued one hundred and twenty-three Federals of the one hundred and fifty-five, including the commander, a Major Johnson, were killed, while the guerrillas lost but four. The guerrillas asked no quarter and gave none, and they frequently scalped and otherwise mutilated the bodies of their victims. Often they rode about with human scalps dangling from the headstalls of their bridles, and, it was said, with human heads swinging by the hair from the pommels of their saddles.

After the Rebels had passed Pilot Knob, the city of St. Louis was in great danger. Owing to the fact that so much guerrilla work was going on in central and northern Missouri, General Rosecrans could not expect much help from that quarter for the defense of the city. But when the Confederates had reached Franklin (now called Pacific), thirty-five miles west of St. Louis, Rosecrans had concentrated within his defenses about fifteen hundred volunteers from various regiments—chiefly recruits—five regiments of Illinois “hundred-day men,” and about seven thousand of the Enrolled Militia of the city, while General A. J. Smith, with four thousand five hundred men, was in supporting distance, only a few miles away. It was reported to the Confederates that Rosecrans had twenty-five thousand men, behind breastworks, with plenty of artillery. This gave further assurance that troops in large numbers had been diverted and drawn from other fields, and that the proper movement now was to throw the invading army between this force and the forces west. Hence all idea of attack was abandoned, and the Rebel army moved rapidly towards Jefferson City.

For nearly a year previous to these events I had been in command of the District of Southwest Missouri, with my headquarters at Springfield, in Greene County, which had long been the principal depot of supplies for the army of the frontier. Early in September I had learned of the invasion, and General Rosecrans had instructed me to place the trains and public property under the protection of the fortifications at Springfield; to put the forts in the best possible condition for defense, using every foot and dismounted cavalry soldier, together with the local militia and citizens, to the best advantage; and to watch the appearance of the enemy in my district, and report the earliest indications of the direction of the coming storm. These instructions were carried out as fully as possible. I was authorized to and did call into active service the entire Enrolled Missouri Militia in the district.

On the 25th of September General Rosecrans ordered me to move to Rolla with all of my mounted force— the prospective route of the enemy having now been somewhat definitely determined upon by him and understood by us—in the same dispatch cautioning me against an attack at or near Waynesville. I set out within a few hours, taking with me a considerable part of the Sixth and Eighth Regiments of Missouri State Militia Cavalry, or M. S. M., the Sixth and Seventh Provisional Regiments of the Enrolled Militia, or P. M. M., which latter regiments in a short time thereafter became respectively the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Regiments of Missouri Cavalry Volunteers; and also the Second Arkansas Cavalry Volunteers. All these troops were residents of southwestern Missouri and northern Arkansas, and many of them had seen service, either willingly or unwillingly, in the Rebel armies. The Second Arkansas was composed very largely of “Mountain Boomers,” as the Confederates were wont to term the Unionists of the Ozark Mountains, and their colonel was John E. Phelps of Springfield, a very gallant and dashing young officer, a son of Hon. John S. Phelps, who for eighteen years represented the Southwest Missouri District in Congress, and who was a leading Union man of his section, commanded a Union regiment for a time during the war, and subsequently, from 1876 to 1880, was Governor of Missouri. The men of this regiment were rather rough and unpolished, but were brave to recklessness, and indeed, my entire command was composed of splendid fighters, many of whom had personal wrongs and injuries to redress upon the Confederates.

I left behind me to garrison the posts of my district a few special details from the above-named regiments, and the Enrolled Militia, which latter organization I had called out for the purpose. The loyal people of Springfield, although they were by this time accustomed to the alarms and the varied fortunes of war, were much disturbed at the prospect and loath to see me and my troops leave them. When I returned they gave to me and my command a splendid reception and ovation, of which I presume I was as proud as Caesar ever was on returning to Rome after his most successful campaigns and conquests in Trans-Alpine Gaul.

I marched rapidly to Rolla over the “wire road,” as the road along which the telegraph ran was called. The distance was one hundred and twenty-five miles, and was compassed in a little more than two days. At Rolla I joined General McNeil, about 10 o’clock a.m., September 28, this being the first union of troops from the West; and by virtue of my seniority I assumed command of our united forces. It was expected that Rolla would be attacked for its supplies by the combined Rebel force, and the place was put in a state of defense, and the troops stood constantly to arms until our scouts reported that the army had moved east from Harrison. At that time, as I have said, Rolla was the terminus of the southwest branch of the Pacific Railroad, and was a place of considerable importance. We did not mean to abandon it or give it up until it was wrested from us. I kept my forces together and well in hand. When Ewing, as before narrated, had, after his battle at Pilot Knob, reached the railroad at Harrison station and was again engaged, I sent him but one regiment (the Seventeenth Illinois Cavalry), but I was within supporting distance practically, and this was enough. Ewing and Fletcher came into Rolla on the evening of September 29, tired and weary, and with most decided opinions as to the formidable character of the invasion and the seriousness of the situation generally.

On the morning of the 30th of September it was known that the Confederates had abandoned their meditated attack on St. Lotus, and had turned westward and were in full march for Jefferson City. Thereupon I marched with my own and McNeil’s Brigade for that point, distant about seventy-five miles northwest of Rolla. Price was marching up the Missouri, along the Pacific Railroad, and his line of march from Franklin—the point where he had turned from St. Louis—to Jefferson was longer than mine; but he had two days’ start of me, and I had to move rapidly to beat him in the race. My route was over a broken, semi-mountainous region, thinly inhabited, and with wretched roads.

As I neared the Osage River, at Castle Rock, a few miles from the capital, a column of the enemy was seen advancing over the hills on a parallel route. Hastening forward, I reached the goal with not an hour to spare. And this brought together three brigades of cavalry on October 3 at Jefferson City, or, if General Fisk’s force is counted, four brigades.General E. B. Brown, of the Missouri Militia, had been in command at Jefferson City, with an inconsiderable force, and General Rosecrans had ordered to his -assistance, from the north side of the river, General C. B. Fisk, who had arrived about the 4th of October with a few hundred men. General Brown had called out the three companies of the “ Citizens’ Guard,” of Jefferson City, and all the able-bodied men, white and black, residing or found in the city were set to work digging rifle-pits and building or completing fortifications. On my arrival the command of the post was turned over to me. The Confederates were at the door, very numerous, very strong, and very eager and confident. They had swept up the river from Franklin, carrying all before them. On the 5th of October General Marmaduke had taken the German town of Hermann, on the Missouri, burned the railroad bridge over the Gasconade River, and captured a train laden principally with Arms and ammunition destined for the defenders of the bridge. Squads of recruits had joined them hourly,, and at Union, the county-seat of Franklin County, there had come in a full regiment of mounted men, commanded by Colonel A. W. Slayback, who a few years since was killed in the office of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch by the present editor of the New York World.

At the Osage River, then low and fordable, a few miles east of Jefferson City, they were met by some detachments of our troops sent out by General Brown, and there had been some sharp fighting. The ball opened on the 5th of October at Prince’s Ford, where the main road from St Louis to Jefferson crossed the Osage, and at Castle Rock, four miles above where I had crossed. Our forces at these fords consisted of a battalion of the First M. S. M., under Major Alexander W. Mullins, about one hundred and fifty of the Eighth M. S. M., and the Seventh M. S. M., under Colonel John F. Philips, now U. S. District Judge for the Western District of Missouri. The troops on the Confederate side were of Shelby’s Division. The Union forces were driven back, though with considerable loss to the enemy, among whose severely wounded at Prince’s Ford was the commander of Shelby’s leading brigade, Colonel David Shanks, who fell a prisoner into our hands. The Confederates pushed back our troops at Castle Rock without much difficulty, and Colonel Philips retired with his command about four miles, to near Jefferson, the enemy following slowly, so as to allow his forces time to come up for the contemplated attack on the capital. Shelby’s Division went into camp in line of battle six miles from town, and General Price himself, with the reserve, came up during the night.

General Fisk was senior in rank, but he said to me that he had never been under fire, and should depend wholly upon me for everything. So, as the commander of the post and the forces at Jefferson City, my position was one of grave responsibility. I did not have under me more than six thousand men, “horse, foot, and dragoons,” volunteers, militia, and citizens, while the enemy numbered fully sixteen thousand men. But I had the advantage of some fairly good fortifications, plenty of ammunition, men in whose fighting qualities I had confidence, and I determined that Jefferson City should not be reentered until my command had been fairly and utterly whipped. The Missouri River was at my back, and I could not well have retreated if I had even entertained the thought. The appeals of women and non-combatants to me to surrender without a fight and save all of our lives as well as the town were most touching, but could not be heeded!

Everything was therefore put in order as well as might be for the expected encounter, and I may say without boasting that I somewhat relished the prospect. Generals Fisk, McNeil, and Brown gave me the fullest sympathy and cooperation, and all the men seemed eager for the fray. There had arrived on the 5th, from the north side of the river, a regiment of newly recruited infantry volunteers—the Forty-first Missouri, I think—mostly from Pike and Lincoln Counties. The colonel of this regiment, D. P. Dyer, then a smooth-faced, fresh-looking young lawyer, “ all the way from Pike,” came to me and very frankly said, 4i General, I have here a regiment of raw recruits, all green in the tactics, but all fine shots and good fighters. They have never been on battalion drill, but they will obey orders to the best of their knowledge, and they will fight to the last before they will run. Now, I want you to overlook our ignorance and awkwardness, and in the fight put us where you think we will do the most good, either in the front or in the rear, and we will do our very best for you.” I designated a position in one of the outer trenches for the regiment, and when the Colonel left he said, u Now, General, when this fight is over, you will find us right there, dead or alive, unless you order us away.” Colonel Dyer has since represented his district in Congress, and is now a prominent lawyer of St. Louis.On the morning of the sixth skirmishing was resumed. It had been decided by us, all the generals concurring, to oppose a moderate resistance to the enemy’s advance across the Moreau, a small creek with muddy banks and a bad bottom, which, south of Jefferson, runs eastward a few miles, then turns north and passes east of the city about four miles and empties into the Missouri. Our troops were expected to retire slowly and in good order to our main defensive line, where the issue was to be fought to a finish. This day the enemy burned the railroad bridge over the Osage, near its mouth, a few miles east of the town.

Early on the morning of the 7th General Price moved against us, with Fagan’s Division in front and Cabell’s Brigade in advance. Our forces, chiefly the M. 8. M., dismounted, met them in good style, fighting them pluckily and falling back slowly. A part of the Sixth Regiment, under Major E. S. King, and the Eighth. Regiment—which I had brought from Springfield— commanded by Colonel J. J. Gravelly, were perhaps-the most actively engaged mid suffered most. Fagan lost pretty severely, and we now know that many of his best officers and men were killed and wounded. I was out to the field, and I know that the skirmishers were stubborn and the fight was very fierce and deadly. It had, I think, the effect of making General Price realize what would take place if all the forces should become engaged. Our covering force having reached the town, I placed the artillery in position at the outer fortifications on the ridge south of the city, and began to shed the enemy, who occupied another ridge to the southeast a mile away. This kept them at a distance, and they did not offer to come to close quarters, somewhat to my disappointment, for we were all quite ready for them. Late in the afternoon they planted a battery on a ridge east of the city, from which they fired a few times; but we responded promptly from a section of one of our batteries which was planted east of the cemetery, and soon drove them away, and thus they learned that we were ready on every side and armed at all points.

It was now apparent that they were moving westward, but whether preparatory to an assault in force on the south and west of our position, or whether to draw me out so as to have me at a disadvantage, or whether they had abandoned the attempt to take the capital, I could not know. I had fought Price before, in Mississippi, at Iuka and Corinth, and on the Oxford campaign, and though I knew he was cautious, I knew he was crafty and wary, and that when he did fight, fought hard. But the disposition of our troops was such that he could not make a vigorous attack upon our lines anywhere without heavy loss.At noon of the 7th General Price concluded to give over his attempt on the capital of his State—where, by the way, he had previously sat as governor for four years—and began to pass his train to the westward. At about nine o’clock the following morning his troops left in the same direction. We were watching them closely, and before they were fairly under way we were in the saddle and out after them. Leaping upon the rear-guard, commanded by a Colonel Schnable, our advance drove it, broken and bleeding, upon the main column. Cabell’s brigade of Arkansans then took the rear, and these we followed and skirmished with until late in the evening.

On this day there arrived in Jefferson City Major-General Alfred Pleasonton, who at the request of General Rosecrans had come on from the East to command the forces in the field in the campaign against Price. General Pleasonton was a graduate of West Point, had spent his life in the army, was a finished soldier, and had already gained high distinction as a cavalry leader, and we were all very glad to see him. He was given all the information we possessed, and at once made his plans.

General Pleasonton placed me in command of all the available cavalry force of the command and one battery of light artillery, and directed me to proceed at once in the direction of the enemy, delay his progress as much as possible until our infantry, under General A. J. Smith, could come up, and to hang upon his flanks and prevent his advance north of the Missouri or into Kansas without a battle, with the combined forces of the Kansas troops and my own command. My command consisted of regiments and detachments of Missouri State Militia Cavalry, Provisional Regiments of the Enrolled Missouri Militia, two regiments of cavalry volunteers and artillery. I immediately organized these forces into three brigades. The First Brigade consisted of detachments of the First Iowa Cavalry, and of the First and Fourth M. S. M., and the Seventh Regiment M. S. M., and was commanded by Colonel John F. Philips, of the Seventh M. 8. M. The Second Brigade consisted of detachments of the Third, Fifth, and Ninth M. 8. M., the Seventeenth Illinois Cavalry, and a battery of mountain howitzers, commanded by Colonel Beveridge, of the Seventeenth Illinois. The Third Brigade consisted of detachments of the Sixth and Eighth M. S. M., the Sixth and Seventh Provisional Militia Regiments, and the Second Arkansas Cavalry, and was commanded by Colonel J. J. Gravelly, of the Eighth M. S. M. The artillery proper, six guns, Captain Charles H. Thurber commanding, was attached to the division generally, to act under my orders. In all, my division numbered about forty-one hundred men, all well mounted and armed.

As soon as it was ascertained that the Rebels were leaving Jefferson, the First Brigade, Colonel Philips, which was already in motion, was ordered to continue to march on the Jefferson City and Springfield road towards Versailles and Warsaw, while the Second and Third Brigades were ordered forward along the line of the railroad towards California and Tipton. General Pleasonton decided to remain in Jefferson to forward reinforcements and attend to other duties, and I was to take command of the forces in the field until he should relieve me. I of course hastened to join the troops, already advancing, but before I could get out of town artillery firing was heard on the Springfield road, showing that Philips had overtaken the enemy and was “at it” again. In a few minutes I received a dispatch from Colonel Philips informing me that the enemy had made a stand at the crossing of the Moreau, southwest of the city, occupying a strong position, with artillery, and that artillery was needed on our side to enable us to carry the position without severe loss. The Second Arkansas had already been sent to his support, and I immediately ordered the remainder of Colonel Gravelly’s Third Brigade, with one section of Thurber’s Battery, to turn off from the California road and move to the support of Philips. The enemy retired, however, from the Moreau before Gravelly could come up, abandoning, besides his killed and severely wounded, about seventy horses. Philips’s loss was inconsiderable. This was the action with the Confederate rear-guard under Schnable and Cabell, before adverted to. The First and Third Brigades and one section of artillery bivouacked on and near the Moreau that night, and the Second Brigade, with the rest of the artillery, encamped at Gray’s Creek, about ten miles from Jefferson, on the California road.

At daylight on the 9th, from his bivouac east of the hamlet of Russellville, the enemy moved forward rapidly on the Springfield road, towards Versailles, my Third Brigade in pursuit. All this day we were at work. The Second Brigade, Colonel Beveridge, moved by a neighborhood road from the road to California to the Springfield road, and advanced to the support of the Third Brigade, which was already engaged with the enemy’s rear-guard. The country east of Russellville was heavily timbered, and while passing through it the enemy resisted our advance strenuously with a heavy line of dismounted skirmishers and strong reserves. Coming up with the Confederate rear, I immediately formed the entire Third Brigade in line, with some dismounted skirmishers in front, and the other brigades moved forward in support. By reason of the protection afforded by the timber and the uneven formation of the ground, the enemy was able to resist the advance of our skirmishers to such an extent that at last it was deemed proper to charge with a mounted force through his skirmish line and attack his reserves. This was accomplished by a detachment of the Sixth M. S. M., under Lieutenant Riley B. Riggs of Company K of that regiment, and the enemy retreated rapidly through Russellville, leaving several dead on the field. Lieutenant Riggs, the gallant officer who led this detachment, fell dead in the charge within five yards of the enemy’s reserves.

The road was now clear to the open prairie, on which, as we emerged upon it, the enemy’s columns and trains were plainly visible, and within cannon-shot. Artillery was immediately opened on the fleeing columns, which continued to move forward towards Versailles, until they had passed every road turning to the right towards California, except the road at a place called High Point, This action on the part of the enemy determined me to move by the shortest route and by a rapid march to California (the first county-seat west of Jefferson City), in order that I might be in position to strike his flank if at High Point he should turn north towards Booneville, on the Missouri, or, if he continued his march towards Warsaw, on the Osage River, south of Sedalia, that I might move rapidly on his flank during the night and reach Warsaw ahead of him.

The head of my column came out of the timber on the open prairie near California about five o’clock in the evening, and found Marmaduke’s Division in the town, a portion of this force being engaged in tearing up the railroad, and the remainder, perhaps two brigades, in line of battle. The enemy at once opened with artillery on my advance, but without effect. Dispositions were immediately made for fight; but I will not weary you with the details. Suffice it to say that in less than an hour we had driven Marmaduke away. As the left of our line entered the town the Confederates galloped off, leaving five dead, while I think we had but one man severely wounded. As it was now dark, and we were all tired, we went into camp at California for the night.

That evening the Confederates entered Boonville, on the Missouri, Shelby’s Division in advance, capturing the small Federal garrison of seventy-five militia quartered in the court-house. The next day Fagan’s and Marmaduke’s Divisions were in and about the town, and the guerrillas from the north side of the river crossed over on the steam ferry-boat of which the enemy had taken possession. These wretches were still gloating over the carnage they had enacted at Centralia, and many of them were said to bear on their bridles the scalps of our soldiers slain on that occasion. A day or two later Price sent Bill Anderson, the most cruel and merciless of the guerrilla leaders, back across the river, with a written order to operate against the North Missouri Railroad, directing him to “ go as far east as practicable.” Two weeks later Anderson was killed and this order was found on his body.

At daylight on the morning of October 10 my command left camp at California, moving through the town of Tipton and following cautiously after the enemy, bivouacking for the night within nine miles of Boonville, on the Tipton and Boonville road. Early the next morning (the 11th) we were again in motion. I sent out columns and detachments on the different roads leading into Boonville from the east and south, in order to ascertain whether all or only a part of the enemy’s forces were in Boonville. One of these detachments was under Colonel Epstein, of the Fifth M. 8. M., whose home was in Boonville, and who knew the country well, as did many of his men. At one time my line was pretty well extended, but our movements had been carefully planned, and no accident occurred.

We kept pushing up, and at last struck the enemy’s skirmishers, driving them back. In the afternoon we had gotten fairly in front of the enemy’s position at Boonville. One of our companies—Company H, Sixth Provisional E. M. M.—under Lieutenant T. J. Gideon, actually advanced into the outskirts of the town and for a time occupied two or three houses for protection. The enemy, now thoroughly aroused, opened with artillery on these houses and on our line, and also brought his main line into action. Our troops held their position as ordered, and fell back slowly in the evening across the Petite Saline, where the entire command bivouacked for the night.

The attack of the Rebel forces in and near Boonville has always been misunderstood or misinterpreted, even by the officers of my own command in some instances. It would have been an easy task to have captured and occupied the town, but it would have been without any military advantage. I had been advised by a citizen in the morning that nearly one-half of the Rebel army had crossed the Missouri River. Artillery firing from a northwesterly direction was heard before noon from north of the river, and I concluded that some small posts in that quarter were attacked, and, small as my command was, I determined at once to move upon Boonville as if it had been determined to fight a general battle, and take the place and the Rebel troops therein if possible, and thereby force the Rebel commander to bring back the force that had been sent north of the river. The movement and attack had this effect—before night ferry-boats were visible on the Missouri transporting Rebel troops from the north to the south side of the river, and it was evident that the entire Rebel force would be concentrated in Boonville during the night. Furthermore, it was a part of my instruction from General Pleasonton to keep the Rebel forces if possible in a section not remote from Jefferson City, but under no circumstances to allow them to get between my command and that place. My command was out of rations, and had been for two days, and a train-load of these supplies was approaching via California Station, escorted by the Thirteenth Missouri Cavalry Volunteers. It was against my orders to risk a general engagement, except in one or two emergencies, of which the present condition was not one. To hazard battle with five thousand cavalry, fighting in a measure defensively, with myself the only general officer on the field, with an army of nearly twenty thousand cavalry, fighting in a measure offensively, and commanded by seven general officers, seemed to me to put to too great hazard all the interest of the government in Missouri and Kansas. Moreover, by falling back ten or fifteen miles my command would come upon our supply train, and be reinforced by one or more regiments of cavalry; and if pursued by the enemy it would have the effect of shortening the distance between that army and the reinforcements coming up under the command of General A. J. Smith. All these circumstances and considerations led me to the conclusion to refuse battle at or near the Petite Saline, when I had reason to suppose that it was fairly offered by the commander of the Rebel army. I may be permitted to add that this was the only occasion in the entire war when a battle was offered that I refused to fight, and this was induced solely by the great and overwhelming interests that were at stake, and liable to be lost if an engagement was fought at that place under the circumstances then existing, while an abundant force to encounter the enemy was at that time supposed by me to be within thirty-six hours’ march.

In reviewing my action on that occasion, which now seems more momentous than at the time, after the lapse of so many years, I am more and more impressed with the correctness of my conclusions, so far as my action had a bearing upon the public interest. It is now certainly known that when I commenced to fall back Shelby’s Division of veteran Rebel cavalry was within four miles of the place where we bivouacked; Fagan’s Division was moving squarely upon my left flank over the road by which I had withdrawn the troops from Boonville, and Marmaduke’s Division was in support of Fagan’s. My officers and men were enthusiastically in favor of fighting, and at no time in the war was I called upon to exercise my individual authority and power to such an extent as when I ordered my command to fall back from the Petite Saline. If, however, my command had been formed in line of battle where it bivouacked, it would have been attacked by eighteen thousand men in about one hour after I left the position. If a battle had been fought it would have been fought desperately, and the losses on both sides would have been great, victory for my command possible, but all chances against me. When, a few days afterwards, I was conversing with my superior in command about this crisis, and the temptation I was under to try it, and how I was kept from it by considerations of public policy only, I received the response, “ Well, Sanborn, the responsibility was all your own; if you had fought and won, it would have made you a major-general in the regular army; but if you had fought and lost, and survived the battle, you would have been court-martialed and shot.”

This movement to the rear was made on the morning of the 12th of October. My command reached the supply train, and the reinforcements coming up to my support about noon, immediately procured four days’ rations and faced about. On the following morning we were back to the place from which we had marched on the morning of the 12th, now reinforced by a brigade of veteran troops, commanded by Colonel E. C. Catherwood, of the Thirteenth Missouri Cavalry, which had escorted the supply train to California, near which point he joined the command and held the advance in this day’s march.

A reconnaissance made by a detachment of Cather-wood’s Brigade, led by Captain Turley, of the Seventh M. S. M., developed the fact that the rear-guard of the enemy had left Boonville on the morning of the 13th, moving westwardly and crossing the Lamine River at the Dug Ford and at Scott’s Ford. The railroad bridge across this stream was burned by a detachment sent out from Boonville for the purpose. The same day the greater portion of General Price’s forces went into camp on the Blackwater and the Salt Fork, in the vicinity of Arrow Rock, on the Missouri, and Marshall, twelve miles in the interior, both in Saline County.

The Confederates were now within the large horseshoe bend of the Missouri, comprising the county of Saline, an old-settled and very rich and productive county, whose broad and grassy pastures, fruitful orchards, fertile fields, well-filled barns, and well-stored smoke-houses stretched out before them

“Fair as a garden of the Lord

To the eyes of the hungry Rebel horde.”The people, too, were sympathetic. Many of the raiders were on their native heath, and many more in sight of their homes, on the north side of the river. General Marmaduke was among the Rebel officers native to the county, and General Price was familiarly known. The people gave the Confederates a generous welcome. The generals and their staffs were regaled on savory chicken dinners, fragrant whiskey toddies, and the best the country afforded generally, while numerous bevies of zealous Rebel ladies swarmed about amiable old General Price and kissed his fat, rosy cheeks with great fervor and much enjoyment! The rank and file were also royally entertained. This sort of reception and entertainment had its effect upon the susceptible old chieftain and his army, and doubtless influenced their stay beyond the dictates of good military judgment, and even sound common sense. They spent five days in Saline County—days which in the end proved to them full of danger and deadly disaster.

On the 15th, from Arrow Rock, General Price sent a force to the north side of the river under General John B. Clark, Jr., who, on the 16th, assisted by Shelby, captured the town of Glasgow, on the north bank of the Missouri, and its garrison of four hundred under Colonel Chester Harding. A considerable number of recruits came into the camps, and several men from this and adjoining counties were actually forced into the Rebel service under the Confederate conscript law. Not until the 18th did the main army move out towards the west. On the 17th General Jeff. Thompson, with one brigade, captured Sedalia, the then terminus of the Pacific Railroad, but only remained in the place a few hours.

Meanwhile our troops of the Department of Kansas, then commanded by General Samuel R. Curtis, were very busy. The commands in the field, under General Blunt, were at Lexington and Independence, watching and waiting, while the hastily organized Kansas militia and home-guards were swarming out to defend the border of their young State. Generals Smith and Mower, with their infantry, and General Winslow’s Brigade of veteran cavalry were making all haste to join me, and we hoped to place the invaders between two fires. General Smith reached Jefferson City on the 14th and followed the railroad westward to the crossing of the Lamine, taking charge of the supplies, which, in consequence of the previous destruction of the bridge by the Rebels, could go no farther by rail.

I was apprehensive that the enemy might move by rapid marches to Lexington and on into Kansas, thereby preventing the organization and concentration of the forces in that State, and at the same time placing so great a distance between his army and the infantry and cavalry then moving to my support that it would be impossible for these reinforcements to join me if I should follow him and become engaged. He would, moreover, under the circumstances, be enabled to avoid a battle with the combined forces then being marshalled against him, or with any command larger than my own.

All my movements, therefore, after the enemy left Boonville, were made with the view of holding him within the horse-shoe bend of the Missouri, before mentioned, until the Kansas troops were organized on the border, and Winslow’s cavalry brigade and General A. J. Smith’s command should get up within striking distance. I held the line of the Blackwater Creek and the Pacific Railroad, being north of both, and moved slowly from one “cork” of the horse-shoe towards the other. With the exception of a small force under Captain Turley, before mentioned, I moved my command by Mount Nebo church through Georgetown, then the county-seat of Pettis County, up the Georgetown and Lexington road to Cook’s store, arriving at the latter point at 3 p.m. of October 15. Here I was in position to resist the advance of the enemy, if he should move south, or to attack his flanks if he should move westward towards Lexington. The detachment under Captain Turley—whose home was in the vicinity, and who knew the country very thoroughly—was ordered to follow upon the enemy’s trail.

Two days of disquietude and dissatisfaction were spent by us in the vicinity of Cook’s store. We were uncertain as to the intentions of the enemy. We knew where he was and how strong he was, and that we dare not attack him; and yet we were impatient to do something. Only that we possessed a goodly store of “the better part of valor,” we would have ridden over the prairies and given the insolent invaders a “turn” anyhow. Detachments from my command reconnoitered the position and movements of the enemy daily and nightly. My principal scout was William Hickok, “Wild Bill,” the real hero of many exploits, and, according to the dime novels, the imaginary hero of many more. Bill was a fine scout and detective. He entered the Rebel camps, was arrested as a spy, and even taken before General Price; but his inordinate nerve and great self-possession not only saved him, but made him an orderly on Price’s staff. He eventually escaped, and returned to me with valuable information during the battle of Newtonia.On the 17th of October certain movements of the Confederates indicated that they were about to move southward through Marshall, and the fact that their advance appeared at Dover, a village ten miles east of Lexington, gave color to the supposition. Upon the suggestion of General A. J. Smith I at once moved south a few miles to a good position on the Black-water, that I might be the better able to strike them if they should attempt to move south. Our subsistence supplies had been exhausted for two days, and it was absolutely necessary to have a supply train from Sedalia. But as soon as the enemy learned that I had moved south to the Blackwater, and that the coast to Lexington was clear, he at once and rapidly began moving westward, and on the night of the 18th had reached Waverly, some eighteen miles from Lexington. I could at any time have done the enemy very serious damage by attacking his flank and rear; but the only effect would have been to induce him to make more rapid marches and place a greater distance between himself and our reinforcements.

On the 19th my command received a supply of rations and was ready for the pursuit. This day I received a dispatch by courier from General Blunt, giving the force and position of the troops from Kansas, and indicating that both he and General Curtis were ready for any emergency. I immediately sent a reply, informing General Blunt of our own position and that of the enemy, and of our intended movements.

At three in the afternoon I received another dispatch from General Blunt, then in Lexington, and to this I immediately replied. Later in the evening, and again on the morning of the 20th, I again dispatched him, giving him full information of the situation, so that he might make every effort to hold the Confederates in check until we could come upon them from the east. I still regard it as the most unfortunate circumstance of the campaign on our side that my couriers and messengers to General Blunt were all prevented from reaching him, and that none of my dispatches were delivered to him. Had he and General Curtis known our position and plans at this time they would have made such a stand, either at Lexington, the Little Blue River, or Independence, as would have enabled us to bring all our forces, including General A. J. Smith’s infantry, into cooperative action, and the entire destruction of the enemy would have been inevitable. Left to his own conjectures as to the situation, and knowing that his own force was largely inferior to that of the enemy, General Blunt fell back from Lexington before the advance of the Confederates, after a moderate resistance, more rapidly than our infantry under General Smith could advance, when, had he known the facts, he would have fought to the last and given time for all our forces to be brought into action.

Also on the 19th I received a dispatch from General Pleasonton that Winslow’s Brigade of cavalry and General Smith’s Corps of infantry had arrived at Sedalia. Winslow’s Brigade was composed of five cavalry regiments, the Third Iowa, Fourth Iowa, Fourth Missouri, Tenth Missouri, and the Seventh Indiana. The entire strength of this brigade at this time is reported at only eighteen hundred. The Third Iowa Cavalry was the regiment of Lieutenant-Colonel John W. Noble, the present Secretary of the Interior of the United States. With General Smith’s Corps were four Minnesota regiments—the Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, and Tenth Infantry—and their arduous experiences on this campaign are yet well remembered by the survivors of these gallant organizations.

[continued in Part 2]

Last changed: Aug 02 2018 at 1:48 PM

Back