Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

Veteran Volunteers |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Jan 19 2016 |

On June 25, 1863, the United States War Department issued General Orders, No. 191, offering incentives for volunteers to reenlist for the duration of the war as “Veteran Volunteers.” Included among the incentives were …

On June 25, 1863, the United States War Department issued General Orders, No. 191, offering incentives for volunteers to reenlist for the duration of the war as “Veteran Volunteers.” Included among the incentives were …

- “Every volunteer enlisted and mustered into service as a veteran under this order shall be entitled to receive from the United States one month's pay in advance, and a bounty and premium of $402.

- “As a badge of honorable distinction, ‘service chevrons’ will be furnished by the War Department, to be worn by the veteran volunteers.

- “A furlough of thirty days will be granted to men who may re-enlist in accordance with the provisions of this order.”

|

Col. Edward R. Winslow |

Sgt. William F. Scott |

Both William F. Scott and Edward F. Winslow mustered into the 4th Iowa Cavalry in 1861. In 1863, both reenlisted as Veteran Volunteers. In their respective memoirs, Scott and Winslow made a point of emphasizing their belief the veteran volunteer reenlistments were a critical component to the success of their campaigns in 1864 and 1865.

Here’s an excerpt from Winslow’s forthcoming memoir, “The Story of a Cavalryman: The Civil War Memoirs of Edward F. Winslow, 4th Iowa Cavalry,” being published in 2016 by Trans-Mississippi Musings Press.

In the autumn of 1863 General Orders of the War Department were published respecting the reenlistment of volunteers who had originally enrolled for three years and who had served more than two years. Such soldiers could again enlist for a further period of “three years or during the war,” and they were to be styled “Veteran Volunteers.” These volunteers would be entitled to a furlough of 30 days, a bounty of $400, and they could wear the service chevron on their coat sleeves. In case three-fourths of the men eligible in any regiment reenlisted, they would have the right to retain their regimental organization and its name. The men of the regiments forming my brigade availed of this privilege.

The situation of the Union armies in 1863 was only redeemed by the great victories of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. There had been many mistakes and misfortunes and it became necessary to assure the future success in the important campaigns of 1864. No more important step was taken than that which led to the reenlistment of men who had served two years. They had experienced the disabilities and learned of the shortcomings attached to volunteers for the first year of service and had become accustomed to serious campaigning during the second year. They knew what war meant. It was realized that such men as these, men of actual experience in camp, on the march and in fighting, were now soldiers who knew how to take care of themselves in camp and in action.

Cavalrymen had found out how to manage, care for and use their arms and horses; men in the artillery service knew how to employ the valuable and effective property entrusted to them. The infantry soldier had become hardened, could march, fight, and employ his gun effectively. He knew the relationship of his arm of the service to the conduct and actions of the others. The soldier of two years had also learned the necessity for obedience to orders, to rely upon his officers and his comrades, and he knew the value of the coordination of the various commands. He believed in himself and his officers and he had discovered that war was a scientific as well as a commonsense business. He had made up his mind that this war was one which must end in the recognition of the Union and that he must see it through to that end. His patriotism had become stronger and was the most important thing in life. He was willing to sacrifice his own life in the great cause and, as he now knew the risks, he could think over the situation and calculate the chances.

When the South was putting forth renewed and strenuous efforts to hold its troops in the ranks and to largely increase their numbers, President Abraham Lincoln turned to the men whose time would soon expire and proposed that they should reenlist for the remainder of the war. He knew these soldiers were now like steel tempered in fire and water. If these men would stand firm, they would become the nucleus around which the new recruits could be rallied. The armies would continue to be veterans in practice, with troops that would manfully enter upon the great campaigns of 1864 and finish the war. President Lincoln trusted the veterans, as he did the patriotism and common sense of the American people, and they promptly responded to his call.

Within two months, more than 146,000 men voluntarily reenlisted for the war, long or short. This large body was perhaps one-fourth part of all the fighting men then actually carrying guns in the ranks. Has the world presented in its modern history such a spectacle? The soldiers did not again enroll their names and offer their services because of the promise of a few hundred dollars and a month’s furlough, although this promise and its fulfillment made it possible for them to see and assist their families. They told at home, and to all they met, their experiences and hopes and did much to arouse enthusiasm.

If we could have questioned these men, we should have learned how earnest they were; how seriously they undertook to continue in the service of their country for the maintenance of the Union, and how little they were moved by the romance and interest in a new career, which had partly influenced them when they first left their firesides to enter upon a life of excitement—when overconfidence had been followed by much unexpected, and often unnecessary, exposure and suffering.

The moral effect of the reenlistment of these men upon those in power in the South and upon the Confederate armies must have been considerable. It encouraged the North and must have discouraged the South. The visits of the veterans to their homes and the fact of their reenlistment certainly affected favorably the vote for and aided in the reelection of President Lincoln in the autumn of 1864. This greatly encouraged the enlistment of additional men. The 4th Iowa Cavalry received more than 500 recruits from Iowa, one of the states where no draft was necessary and one which furnished 70,000 volunteers during the war.

|

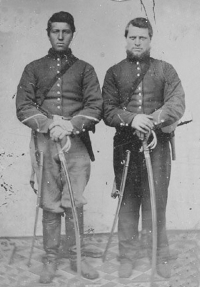

Robinson brothers, 1st Maine Cavalry. Lefthand brother is wearing the veteran volunteer service chevrons |

Unidentified corporal wearing veteran volunteer service chevrons |

Last changed: Jan 19 2016 at 1:12 PM

Back