Search:

Powered by

Website Baker

Yet Another New book from Trans-Mississippi Musings Classics |

| Posted by The Muse (themuse) on Dec 26 2013 |

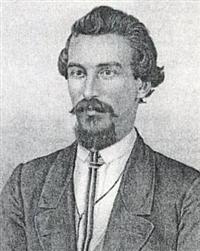

The Civil War Classics series from Trans-Mississippi Musings brings the best of the works by authors who were present during the American Civil War in those states and territories west of the Mississippi River. These are public domain works, which I have reformatted as eBooks. One of the best regimental histories available is A Southern Record: The History of the Third Regiment Louisiana Infantry published in 1866 by William H. Tunnard.

Born on March 14, 1837 in Newark, New Jersey, Will Tunnard grew up in Louisiana after his parents moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana in 1839. Will was twenty-three years old, working in the newspaper business, when Abraham Lincoln was elected President of the United States. When the Louisiana General Assembly passed legislation in December 1860 to organize the State Militia, Will Tunnard volunteered for and joined the Pelican Rifles. The Pelican Rifles were part of the State Militia force that Louisiana Governor Thomas O. Moore used to capture the Federal Arsenal in Baton Rouge. Less than a week later, the Louisiana State Convention had voted to secede from the Union. Thus, Will was involved in the American Civil War from the very beginning. Will Tunnard made good use of his experience as a newspaper man. Throughout the war, Will kept a diary, which he used to write this regimental history.

Having joined the Confederate States of America in February, Louisiana was ready to provide men to fight for the Confederacy following the capture of Fort Sumter in April. On May 17, 1861, the Pelican Rifles became Company K in the Third Louisiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment, with Will Tunnard as one of its Sergeants. The regiment elected Louis Hebert of Baton Rouge as its Colonel. Tunnard’s father was elected to be the regiment’s Major.

"This Regiment, numbering 1,085 men, were the bone and sinew, some of the choicest spirits from the parishes which they represented, mostly young men, with the glow of health upon their features and the fire of a patriotic devotion and enthusiasm sparkling in their clear eyes; men who went forth actuated by a firm conviction of right, earnest adherents to principle; whose brave spirits met the issue squarely, and would not quail or flinch when the day of danger and trial arrived. Strange as it may seem, this organization of robust young men were commanded by field officers whose heads were streaked with gray men of age and experience."

The Confederate War Department assigned the Third Louisiana to the McCulloch Brigade, under the command of Texan, Brigadier General Ben McCulloch. Initially, McCulloch was responsible for preventing an invasion of the Indian Territory by United States forces. But events in Missouri soon pulled the Third Louisiana into the Missouri maelstrom. In June 1861, Federal volunteers under the command of Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon sent Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson into exile and defeated the Missouri State Guard in the Battle of Boonville. The Missouri State Guard was retreating south and in danger of being driven out of Missouri and into Arkansas. McCulloch made a decision that would change the course of the war in the Trans-Mississippi. He moved north into Arkansas and Missouri to support the pro-Southern Governor and Missouri State Guard.

Will Tunnard and the Third Louisiana joined up with the McCulloch Brigade at Camp Jackson near Maysville, Arkansas. Not too long after the Third Louisiana arrived at Camp Jackson, Brigadier General Ben McCulloch rejoined his command there. The brigade moved east towards Bentonville, Arkansas. Tunnard is very effective when he describes life in the Confederate Army. He describes the march and conditions in the camp established east of Bentonville.

"The troops were once more under marching orders, and at 8 a.m. next morning left Camp Jackson for Bentonville, distant 28 miles. There were about three thousand men on the road, which was terribly dusty, and the weather, as usual, clear and sultry … On the 14th passed through Bentonville, a small but pleasant village, situated in Benton County, on the outskirts of an extended prairie … As usual, springs of cool, clear water were abundant along the route. Marched 12 miles. On the 15th we encamped amid the hills of Arkansas at a spot known as Camp McCulloch, being a small field on the level surface of one of the numerous rocky promontories of the country. The rain poured down in torrents, and we began to experience some of the inconveniences of a soldier’s varied existence. The men made beds of the rails from a worm-fence close at hand, to keep their bodies from the damp ground, covering their rough edges with straw and shucks, which they deemed an especial luxury, and upon which they laid down to pleasant dreams. Receiving marching orders early the next day, the troops moved forward a short distance and encamped on Sugar Creek, a small mountain stream winding its tortuous way amid the surrounding hills. This was known as Camp Stephens, in honor of our Vice-President, being seven miles east of Bentonville … The weather was unusually fine, our encampment pleasant, yet many of the extra duty men will remember the severe labor of clearing a parade-ground where they obtained their first experience in digging up stumps and grubbing out roots. While remaining here a tremendous storm occurred at night, flooding the camp with water, which flowed in a miniature river through its center, sweeping away pans, basins, tables, etc. Amid the lightning’s vivid flash and the deep roll of the thunder could be heard the shouts of the men, exclamations and expletives, as they were literally drowned out of their beds."

While at Camp Stephens, they learned that Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon’s Federals occupied Springfield, Missouri. McCulloch assumed command of a coalition of Southern forces, the Confederate McCulloch Brigade, the Missouri State Guard under the command of Major General Sterling Price, and an Arkansas Brigade under the command of Brigadier General N. Bart Pearce. Moving into Missouri to attack the Federals, the Southerners were surprised by Lyon early on August 10, 1861. The Southerners rallied and defeated the Federal army. Will Tunnard’s Third Louisiana fought bravely throughout the day, playing a key role in the victory. Tunnard wrote about the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (called the Battle of Oak Hills by the Confederates).

"The Battle of Oak Hills enlightened many ignorant minds as to the seriousness and fearful certainty of the contest. It did not, however, unnerve a single arm to strike a fresh blow, or dampen the ardor of a single heart. It proved thoroughly the dashing bravery of the Southern soldier, contending under every disadvantage against almost inevitable defeat, and taught the enemy also a severe lesson of what the future contained. So sudden and unexpected the attack, so close, terrible and obstinate the contest, that numbers thought the day irretrievably lost and gave up in hopeless despair. Not so with the Louisianans, who never for an instant felt that they were whipped. Through the thickest and hottest of the fight, where shot and shell fell fastest, and the rifles poured their storm of leaden hail, the regiment forced its way, charging the foe with loud cheers, and always driving them from their positions. For more than six hours the desperate conflict continued, beneath the cloudless sky and in the sultry atmosphere of an August day."

After Oak Hills, McCulloch withdrew from Missouri into Arkansas, and the Third Louisiana went into winter quarters at Cross Hollows, about 7 miles southeast of Bentonville, Arkansas. Tunnard described the conditions of the Confederate encampment.

"The quarters of the Louisiana Regiment were situated in one of the valleys of Cross Hollows, protected from the chilly, wintry winds by high, rocky hills, covered with a heavy growth of timber. They were substantial wooden buildings, constructed of tongued and grooved planks placed upright, with roofing of the same material. The flooring was the very best, and would have been a credit to the handsomest of private residences. Each building was 38 by 20 feet, divided into two rooms by a partition meeting in the center at the chimney, constructed of brick, with a fire-place in each room, with a smooth brick hearth. The privates’ quarters were in two parallel rows facing each other, while the officers ran perpendicular to them, forming a square at one end. The men were not too much crowded, and slept in berths placed one above the other, similar to those in a state-room of a river steamer. The utmost contentment and good feeling prevailed among the men, and all seemed determined to enjoy the days of the winter months. With abundant material for the purpose, they soon manufactured chairs, tables, shelves, and mantle-pieces over the fire-places. Most agreeably were they disappointed at their situation and surroundings. They soon gathered about them all those little comfort’s and conveniences which so materially contributed to the happiness of a soldier’s precarious existence. The buildings were soon named according to the inclination of the occupants, and a stroll through the quarters exhibited to the view grotesque lettering, telling of all kinds of “Dens,” “Retreats,” and “Quarters,” while you could easily discover “Bull Run,” “Leesburg,” “Belmont,” and other streets. “Manassas Gap” opening into “Capital Square,” the officers’ quarters."

As Christmas approached, the Third Louisiana amused themselves in the snow.

"[On December 22] there was a heavy fall of snow. A scene of uproarious mirth ensued. There was a general “ducking” of all, irrespective of rank, and fierce battles with snow-balls. It was hazardous for anyone to venture in sight, as he would be most unmercifully pelted with snow …

"Christmas Eve, the holiday festivities, and foaming bowls of egg-nog, with raw liquor, seemed as plentiful as the spring water nearby. Uproarious hilarity prevailed, the absent were toasted in many a cup, and songs sung with eventually discordant chorus. The next day was Christmas. Soldiers loved to dispense hospitality, consequently there were numerous gatherings of convivial spirits, and egg-nog was drank with all the eclat and formality of a drawing-room assembly, or hilariously tossed off with a jovial toast and upraised cups."

Next came the Battle of Elk Horn Tavern (Pea Ridge), which took place in early March 1862. Once again the Third Louisiana was in the thick of it. Tragically, Ben McCulloch and his second in command, James McIntosh, both were killed during the first day’s fighting. The Third Louisiana lost its commander, when Colonel Louis Hebert was captured by the Federals. Confusion reigned supreme on the Confederate left. In the second day of fighting, running low on ammunition, the Confederate commander, Major General Earl Van Dorn, ordered his army to retreat. When the fighting was done, the Federals remained in possession of the field and secured the victory.

The Third Louisiana next left the Trans-Mississippi, crossing the Mississippi River to fight in the Battles of Corinth and Iuka. Eventually, Will Tunnard and the Third Louisiana found themselves in the earthworks of Vicksburg, Mississippi, under siege by Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee. At first, the Third Louisiana did not believe events would take a turn for the worse.

"The 17th of May dawned clear and warm. The bright, smiling skies seemed not as if they canopied events which would decide the destiny of a great nation … The troops left Snyder’s Bluffs for aye late at night, and proceeded toward Vicksburg, an intermingled line of wagons, artillery, and infantry. The night was very dark, yet the men pushed forward as rapidly as possible along the valley, wading streams and sloughs on the route. Notwithstanding the gloom which overshadowed their future, and the losses which they had sustained by their sudden abandonment of their recent position, as well as the proximity of the foe in such overwhelming force, they were in most excellent spirits, and very enthusiastic. They considered Vicksburg an impregnable strong hold, and experienced a peculiar pride in the prospect of defending it during the approaching struggle."

But the Third Louisiana suffered terribly during the 48-day siege of Vicksburg, and were on the brink of starvation by the time Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton surrendered to Grant. Will Tunnard described the regiment’s reaction to the news of the surrender.

"The receipt of this order was the signal for a fearful outburst of anger and indignation, seldom witnessed. The members of the Third Louisiana Infantry expressed their feelings in curses loud and deep. Many broke their trusty rifles against the trees, scattered the ammunition over the ground where they had so long stood battling bravely and unflinchingly against overwhelming odds. In many instances, the battle-worn flags were torn into shreds, and distributed among the men as a precious and sacred memento, that they were no party to the surrender."

For a short time, the men of the Third Louisiana were prisoners of war. Then they were released on parole, swearing on their honor that they would not serve in the Confederate army until formally exchanged. After this the regiment began to “melt away.”

"The mass of the regiment had already left the army, and, crossing the Mississippi River wherever this object could be successfully accomplished, had made their way homeward in small squads. The greater portion of the command resided in parishes west of the Mississippi River … The conduct of the Third Regiment in thus voluntarily disbanding was not the exception, but the general rule in the army. The men who had fought so long and bravely, and who had suffered so severely, felt, after their capture and paroling, as if they were not only exempt from all military duty, but privileged to go where they pleased, and do as they pleased, until exchanged. They sadly needed rest and recreation, and sought their homes, as being the most favorable places to obtain these most desirable objects. Thus melted away the gallant army of Vicksburg, and the Confederacy lost the services of some of her bravest, most heroic, and truest defenders. General Grant could not have employed a more efficient method of disbanding and disorganizing an army than the very course he pursued. It was as effective as if a scourge had swept them from his path."

Spending over a year on parole, Will Tunnard never did return to any action of consequence. The end of the war for the Louisianans came on May 10, 1865 when General Kirby Smith formally surrendered the Confederate forces in the west.

"On the 10th of May Camp Boggs presented a strange spectacle. The men were gathered in groups everywhere, discussing the approaching surrender. Curses deep and bitter fell from lips not accustomed to use such language, while numbers, both officers and men, swore fearful oaths never to surrender. It was such a scene as one seldom cares to witness. The depth of feeling exhibited by compressed lips, pale faces, and blazing eyes, told a fearful story of how bitter was this hopeless surrender of the cause for which they had fought, toiled, suffered for long years. The humiliation was unbearable."

I hope you enjoy reading Will Tunnard’s descriptions of the Third Louisiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment’s exploits during the American Civil War.

Last changed: Dec 26 2013 at 3:27 PM

Back